Political scientist Catherine Schulman about favorite books

IN BACKGROUND "BOOK SHELF" we ask heroines about their literary preferences and editions, which occupy an important place in the bookcase. Today a political scientist, an associate professor at the Institute of Social Sciences of the RANEPA, a member of the Human Rights Council Ekaterina Shulman is talking about favorite books.

INTERVIEW: Alice Taiga

PHOTO: Alyona Ermishina

MAKEUP: Julia Smetanina

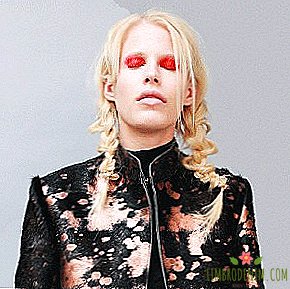

Catherine Shulman

political scientist

Fiction - the highest manifestation of the human spirit, which is already there. She is our mother and nurse, and support us for all the days of our lives.

It happens that a person has read some text - and his life has changed dramatically. For me, the beginning of being a person was rather the very fact of independent reading. As more or less of all the children of intellectuals, I was taught to read at the age of four, and since then, in general, I haven’t been doing anything else. We all belong to the estate that earns a living by reading and writing.

It happens that a person has read some text - and his life has changed dramatically. For me, the beginning of being a person was rather the very fact of independent reading. As more or less of all the children of intellectuals, I was taught to read at the age of four, and since then, in general, I haven’t been doing anything else. We all belong to the estate that earns a living by reading and writing.

Since then, there have been several not so much books as corpus texts that really influenced the way of thinking. First, the Soviet popular science literature. There was a two-volume encyclopedia "What is? Who is this?". There was a book by Ilyin, who in fact Marshak is Samuel Marshak's brother, "How a man became a giant." This is a book about scientific and technical progress, about the development of human thought, science and technology from primitive times, and it ends with the burning of Giordano Bruno. There was an indispensable Kun with the "Legends and Myths of Ancient Greece." There was even Perelman with "Entertaining Physics" and the ten-volume "Children's Encyclopedia", yellow. These are the fruits of the bright era of the sixties, progressive technicalism and the cult of science, which the Soviet government encouraged at that time.

I read a lot of animal literature in my childhood. I had a book "Entertaining zoology". There was a four-volume translated encyclopedia "The joy of knowledge" - with luxurious illustrations, maps and diagrams of how different ecosystems are arranged. Even if these sciences will not mean anything to you, this way of comprehending reality itself, a kindly interest to it and at the same time rationality have something very charming in themselves. From this comes respect for science, respect for the human mind, faith in progress, and the conviction that reality is knowable. So I'm an atheist, not an agnostic.

I cannot name a book that would directly make a political scientist out of me. Interest in politics was natural in those years when I was growing up. It was an era now forgotten - the end of the eighties and nineties, when everyone wrote out many newspapers and magazines, watched political television programs, which then were not at all what they are now. I remember the magazine Ogonyok, the thick magazines Druzhba Narodov and Znamya, the young early Kommersant before Boris Berezovsky bought it - and I remember what this all meant to those who read it.

In order not to create the impression that I was brought up by perestroika journalism, it is necessary to mention books that teach a systematic, procedural view of historical and political processes. For me, a very important author was Eugene Tarle. The letter will not matter how his last name is pronounced, but later I was told by people who knew him that he was actually Tarle. The houses were his books about Napoleon, Talleyrand and the war of 1812. There was also a book by Manfred "Napoleon Bonaparte", but this was significantly lower in the class. "Talleyrand" Tarle especially impressed me. There was also a wonderful book about Napoleon, but in that which dealt with the conflict with Russia, even at a tender age I could see the pressure of the Soviet ideology. Talleyrand didn’t particularly disturb anyone, he was definitely a negative character, there was no need to breed patriotism - it was a book not so much about a diplomat as about internal political intrigue. Of course, all this was based on the Marxist view of the historical formations and their change, but at the same time it was terribly charming and informative, and stylistically.

Then, when I was already older, I began to buy other books by Tarle, which are not so well known and not so often published: for example, he had a wonderful work on colonial wars, more precisely, on great geographical discoveries and their consequences for European countries, and the book about the First World War - Europe in the era of imperialism. Already being an independent working girl in Moscow, I bought in the antique department of the shop "Moscow" on Tverskaya a twelve-volume collected works of Tarle for the terrible money for me then. It was even harder to take him home from the store by subway. I am very glad that I did it then - now this blue monumental collection of works of the author, to which I am very much obliged, stands.

My second favorite historian is Edward Gibbon. Reading to the end "The Decline and Death of the Roman Empire" is extremely difficult, and I myself was stuck on Justinian, but his style and logic are irresistibly charming. By the way, much later, I realized that it was he who was stylistically, and not one of the previous novelists, the real father of Jane Austen.

I have always with some disdain for people who say that "with age" they began to read less fiction, because they are drawn to all that is genuine and real. An artistic text is a complex text, and with any kind of text memoir it will always be easier: no matter how well written they are, they still have a linear composition. This is always a form of telling a life story in a more intellectual envelope. And fiction is the highest manifestation of the human spirit, which is already there. She - our mother and nurse, and support us for all the days of our lives. Nevertheless, when you look at your reading lists, it turns out that even if you do not take professional scientific literature and megabytes of bills and explanatory notes to them, then you read an extremely large amount of memoirs and historical non-fiction. I’ll name my old and new favorites: De Retz, Saint-Simon, Larochefoucoux, Nancy Mitford about Louis XIV, Voltaire and Madame de Pompadour (about Frederick the Great, it seems to me, she didn’t have a very good book), Samuel Pips about herself, loved Walter Scott about the Scottish history, Churchill about the great-grandfather of Marlborough, Peter Aroyd about everything (Shakespeare's biography is good, the new volume of The History of England recently arrived).

But among the literature, the author of my soul is, of course, Nabokov. Here it was a significant transformational shock, but not one-time, but gradual. This is the author who best meets my emotional and intellectual needs. Nothing has changed: how much I read it, somewhere since 1993, I continue to read so much. The last incredible gift - Alexander Dolinin’s commentary to “Gift”, released at the end of 2018. I had the good fortune to get this capital work one of the first ones, by acquaintance, and even record an interview with the author when he came here. I very quickly read the entire volume: it seems thick, very heavy, and when it ends, I want it to be even thicker. If Dar himself is pure joy, then Dolinin’s comment is distilled joy. Just reading - and you envy yourself.

I do not like many of those who like others - and this is not surprising. I do not like Dostoevsky (and the diluted torture of him — Rozanov), I absolutely do not see in him an artistic component, but I see a conjuncture, commercial writing and violent emotional impact on the reader, which usually annoys me too. It is known that in Russia Tolstoy and Dostoevsky are two parties (apparently, in the absence of political parties, people are segregated in this way). And I, of course, belong to the party of Tolstoy - certainly not to the party of Dostoevsky. And the famous dichotomy of "tea, dog, Pasternak" vs "coffee, cat, Mandelstam" in my version should sound like "tea, children, Shakespeare." Although Mandelstam is, of course, a great poet.

Whom do I still not love? Well, to insult everyone like that at once - let's hurt everyone! I am always worried when a person praises the Strugatsky brothers: if these are his favorite authors, I will suspect him of a person, let's say, non-humanitarian, a representative of the Soviet engineering and technical intelligentsia. These are good people, but they do not understand what literature is. Because it is very Soviet literature. And Soviet literature is the work of prisoners. They are not to blame for this, they are the least to blame. They achieve outstanding results in their carving in a glass and making a spoonful of an artistic object from the handle - but all the same, it all breathes in prison. Therefore, I read Soviet writers: their philosophy seems superficial to me, artistic skill is dubious. I also relate with a certain tenderness to the novel “Monday Starts on Saturday”, because this is a description of a certain narrow, specific social stratum and its way of life, and this is its charm. And everything else - in my opinion, this is a deep philosophy in small places. And I repeat once again, I do not grope there artistic fabric.

And there are things that are considered to be lauded, but they are not. "The Master and Margarita" - the great Russian novel. Bulgakov is generally a very significant author, both by himself and as the heir to a whole large layer of Russian prose, about which we have a vague idea, because the Soviet government cut all this out, leaving only the authorized poles with the heads of the classics of the school canon to hang around. For some reason, I also love Theatrical Romance, which seems strange to me: I’m not so indifferent to the theater, but I don’t understand why it exists. Little that leads me to such anguish as stories about actors, theatrical stories and that’s all: I don’t understand why I can play on the stage something that can be read by letters, and why all these people do what they do. But "Theatrical Novel" very much falls on my soul.

And second: Ilf and Petrov, compromised by excessive quoting, are in fact also extremely large writers. Nabokov valued them, called them a "double genius" (he was generally attentive to Soviet literature). The Golden Calf is a beautiful Russian romance, and The 12 Chairs, too, although slightly weaker. So when they say that this is overpraised, no, that is not really. These are genuine values that will pass over the centuries envious distance.

The well-known dichotomy of "tea, dog, Pasternak" vs "coffee, cat, Mandelstam" in my version should sound like "tea, children, Shakespeare"

M. Ilyin (Ilya Marshak)

Encyclopedia "What is? Who is?", "How did a man become a giant"

From these two books lead, I suspect, atheism, and faith in progress, and general reverence for the invincible human reason.

Alexandra Brushteyn

"The road goes into the distance ..."

Although with later re-readings, there began to be a feeling of vague discomfort, but you did not pick out what you read in childhood back - and it is not necessary. In general, the book is about the fact that you can laugh for ten minutes at the whole street under someone else's fence, just as before, - I did not tell them about it ...

Michel Montaigne

"Experiments"

Skepticism is such skepticism. Well, the idea that there is nothing unusual in death.

Eugene Tarle

"Napoleon", "Talleyrand"

The basis of the previous - elitist - period of my political views. The current, democratic, formed without any books, direct professional experience. And once I was a Bonapartist, yes.

Bertrand russell

"History of Western Philosophy"

For delivery of candidate and general clearing of the head. Although the author as a public figure has many complaints, this book is beautiful.

Jane Austen

"Feelings and Sensitivity", "Emma"

The one who thinks clearly, clearly states. There would be somewhere to stick Pope "An Essay on Man" and Gibbon, but they no longer fit. Austin, after all, about what? About personal courage, about looking in the face of self-deception, disappointment and death itself. There is some connection between this quality and the inclination towards absurd humor (another example is Harms).

Vladimir Nabokov

"Other shores", "Comments to" Eugene Onegin ""

What is not "Dar"? But for some reason, not "Dar." I'd rather add "Pale Fire" - apparently, the comment form itself is fascinating for me.

Lev Tolstoy

"War and Peace"

I love “Anna Karenina” more, but “War and Peace” was postponed more: it was read at the time when it was more postponed.

John tolkien

The Silmarillion, The Hobbit

Plus all countless to them marginal. Books about the beauty of the outside world, oddly enough, and the eternal sadness of the immortals. And about the inherent freedom of people who are free to die and are not attached to anything.