Comme des filles: Ray Kawakubo and her feminist fashion

Imagine you are an exemplary editor. respected fashion gloss. It happens in 1981, and you come to the show of a little-known Japanese designer, who settled in France just a year ago, opening the first boutique of the brand in Paris, and she’s her own first-time fashion show. For the sake of completeness, it is worth remembering what happened in the fashion of that time, which focused on conventional femininity and sexuality: the bourgeois beauty of Yves Saint Laurent, the provocative femmes fatales performed by Thierry Mugler, the seductive dresses of the rising star Azzedine Alaya, leaving little room for imagination.

The collection, which critics contemptuously dubbed "Hiroshima chic," predictably did not cause mass approval, but forever changed the fashion world

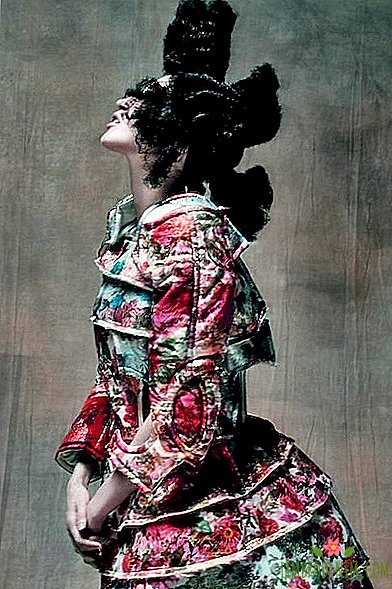

And here yesterday’s student of Tokyo University Keio Ray Kawakubo bursts into the calm, measured rhythm of Parisian fashion with the destructiveness of a tsunami. During the show, girls in indistinct clothes of black color come out to the podium: sweaters, artistically decorated with holes, as if they were eaten properly by moths, flowing skirts and voluminous shirts that hide even a hint of secondary sex characteristics. Honorable public in shock - what was it: things that are supposed to be worn, or an artistic statement on the topic of Japanese devastation after the Second World War? The collection, which critics contemptuously dubbed "Hiroshima chic," predictably did not cause mass approval, but forever changed the fashion world. And hardly anyone could have imagined that Kawakubo would be destined to become one of the most influential designers for many future generations.

To understand Ray Kawakubo as a designer, you first need to know her background. Her childhood and youth came in the post-war years, when Japan withdrew from World War II weakened politically and financially. The seventies, as well as for the UK the sixties, became for the country the formation of a new generation that did not catch the horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki at a conscious age, but living against the background of their social consequences. During the American occupation of Japan in 1945-1952, Westerners sought to impose their own values on the country, in particular, to give women more rights and freedoms. Thus, the new constitution of Japan, which came into force in May 1947, guaranteed women electoral rights for the first time in the country's history. This step was a prerequisite for the feminism movement formed in the 1970s in Japanese society - the very one that would become the catalyst and driving force for all of Kawakubo’s work.

Of course, Kavakubo was by no means the first designer to propagate the ideas of feminism in fashion and try to escape from the generally accepted ideas about femininity and beauty. We all remember Gabrielle Chanel, who insisted that the female figure was not at all obliged to have an hourglass shape in order to be considered attractive, and excessive adornment was a sign of bad taste. Or about Sonya Rykiel, who in a less radical form proclaimed the right of a woman to dress for herself, and not to attract male attention. But it was Ray Kawakubo’s voice that sounded loud enough to echo in the collections of many other designers ten, twenty, and thirty years later.

Kavakubo herself told that during her youth she had to face misunderstanding and disapproval of society more than once: then, in the 1960s, in the still patriarchal Japan, a woman who chose a career instead of a family was considered a close egoist. "I never stop fighting - anger is born in me, and it becomes my source of energy." It is important that provocation in the Kavakubo collections has never been an exclusively visual creative device: the idea of a strong woman who was not obliged to consider attractiveness in the eyes of a man as an end in itself, to bare or emphasize the curvatures of her body, was always behind the apparent oddities.

Exploring the issue of physicality (the most vivid example is the spring-summer 1997 collection), Kawakubo questioned the ideals of beauty imposed by the Western, in particular, American, society, which she personally encountered while living in post-occupation Japan. As her design tools, she used various techniques that somehow went against the conventional norms of the French fashion of the time: deconstruction of clothing elements neatly sewn in the correct order, raw edges and things turned inside out as a metaphor of the wrong side of the fashion industry, mixing male and female in collections. But behind all this there was always an image of a strong and independent of the pressure of stereotypes of a woman, who became the leitmotif of all Kawakubo's work and reflected in the works of designers who admired her.

So, Miuccia Prada, who is called one of the main feminists of modern fashion, has repeatedly said that the founder of Comme des Garçons was for her a huge source of inspiration. The first collection she showed in 1989 was stylistically far from Kawakubo’s complex designs, but she carried the same idea of unconventional femininity in spite of the established canons of the fashion industry of the time. Prada had his own prerequisites for this: an active feminist position, a doctoral degree in political science. But to create her own design aesthetics, which she dubbed "ugly chic", she was inspired in many ways by Kawakubo - the idea of anti-sexuality and the leveling of the very principles of "luxurious" fashion.

Another good example is Alexander McQueen, for whom the Japanese designer was almost an idol in the flesh. His style, especially in more mature years, was different from both the Comme des Garçons and Prada, but the values that he transmitted through his collections were all the same. A strong (often in the literal sense of the word - remember the ending of the fall-winter show -1998/1999) a woman endowed with unconcealed, sometimes frankly aggressive sexuality, an almost mythical creature - an image that is far from popular ideas about beauty.

Almost all the key designers who defined the look of the 1990s in fashion, including Helmut Lang, Martin Marghela, Gilles Zander, and the Antwerp Six, somehow transferred Kawakubo’s ideas to their collections: someone, releasing models on the catwalk clothes are ten sizes larger, someone is creating a minimalist uniform for girls careerists. It does not matter how visually their works intersect with the Comme des Garçons collections: when we talk about the influence of the designer on the minds of her followers, we mean first of all the concept of feminism as the liberation of a woman from dogma to look beautiful and sexy in the eyes of a man.

Many consider the work of Kawakubo close to art rather than fashion: the majority of its collections look too far from traditional concepts about clothes. The designer herself saw in them rather the material articulation of her ideas - about gender, the role and place of a woman in modern society, her right to look like she wants, without looking at the opinion of a partner.

Many consider the work of Kawakubo close to art rather than fashion: most of her collections look too far from traditional concepts about clothes

If you think about it, the fashion of the last three years at least tells us the same thing: against the background of social landscapes formed by a new wave of feminism, Kawakubo’s ideas look like colored black and white films half a century old. It turns out that we have already passed all this, and the foundation of the modern feminist-oriented fashion was laid more than three decades ago. This is not about the notorious T-shirts with slogans, but about the fact that women are reminded again: you can dress as you like, and this should not level your attractiveness or self-confidence, or even characterize you at all.

Today we have a whole cohort of designers who follow the same principles that once transmitted to the world of Parisian fashion Kavakubo: this is Phoebe Faylo, skillfully creating the image of a modern feminist, and Nadezh Van Tsybulski, perfectly fitting the Hermès aesthetics, and Christophe Lemaire , and Consuelo Costiloni, and Chitose Abe. They all can not be brought under a single stylistic denominator, but in an ideological context, all of them are somehow similar.

The exhibition of the Metropolitan Museum "Rei Kawakubo / Comme des Garçons: Art of the In-Between", as stated in a press release, aims to analyze the duality in the works of Kawakubo: fashion / anti-fashion, design / lack of design, high / low, and so on. Surprisingly, in this list there is no mention of one of the main issues of creativity of the Japanese designer - the freedom of women. "Many designers cultivate the idea of what, in their opinion, men want to see women," Kavakubo said in an interview. She had enough courage and talent to offer her own, different from the traditional look and inspire others to do the same.

Kawakubo (as well as Yoji Yamamoto at the same time as her) showed that for a woman, clothing does not have to be a means of decorating or improving herself, but can be a tool for self-expression or protection. Modern fashion continues this idea, adding to it ideas of convenience, comfort as the main value - as a result, we increasingly see things on the catwalks of free cut instead of cocoon dresses and sneakers or flat shoes instead of suicidal heels.

And yes, no one cancels the same Balmain and Elie Saab with their army of loyal customers, Instagram divs, who chose Kylie Jenner as their role model, and women who still prefer to have two diametrically opposed wardrobe styles: “for themselves and meetings with friends and for men. But the beauty of the world in which we live today is precisely in the absence of categorical concepts about what is right and what is wrong. And who knows, perhaps, if not for that show of 1981, the modern world would be a little different.

Photo: Comme des Garçons, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Alexander McQueen