Unforgivable Luxury: Why Couture Everything is Possible

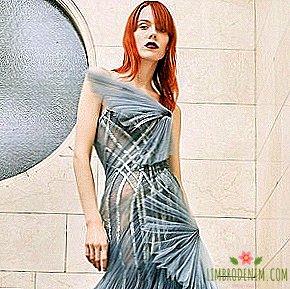

Last thursday in paris ended spring and summer High Fashion Week. Dior was shown a nymph-populated garden, Chanel had dozens of uniform costumes and cocktail looks, Atelier Versace refused to show and took off a book, and Elie Saab made a collection of dresses embroidered with crystals, in which you can walk around the Taj Mahal and not shake. And all this couture. The average cost of one such thing varies from fifty to two hundred thousand dollars. Wedding dresses are more expensive - they say their price tag may exceed one million. Now, in 2017, it sounds like stories from archival magazines about Parisian fashions, when women rustled with silks, dressing for dinner.

But all this is still happening. And although the number of couture customers over the past eighty years has decreased from forty thousand to several hundred people, although with an approximate annual turnover of $ 700 million, sales of couture make up only 1% of all sales in the fashion industry, although haute couture is constantly buried, it is alive and well are buying. Who buys, why and why - these are unanswered questions: if there are no people in your surroundings who wear such things, it’s impossible to learn anything reliably. French law does not allow to report on sales of couture, because it marks it as a “craft”, and brands themselves do not tell anything - neither about specific numbers, nor about customers (there is a version that they ask to hide their names, because they are afraid they were not robbed).

It seems that this world, where the tailors have a measuring tape slung over their shoulders and the ceilings decorated with stucco molding, has closed on itself, but this is not so. Couture is changing, and it is forced to change: every year more and more ideological issues come to it, and it is becoming more and more difficult to make such a priori conservative clothing segment.

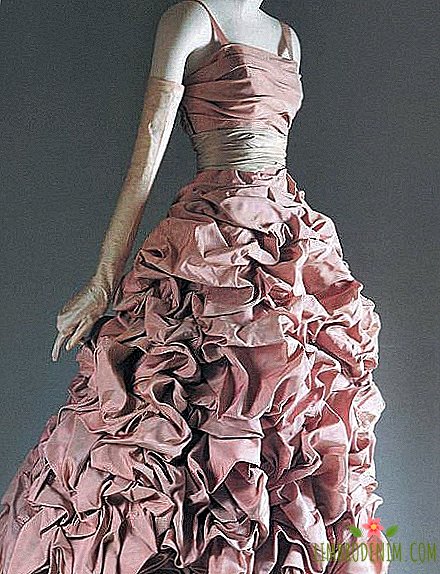

The date of haute couture is considered to be 1858, when Charles Frederick Worth opened his first Paris store. Then, of course, there could be no questions: everyone understood, why and who needs couture. Couturiers wore very rich clients, providing them with a complete wardrobe set - up to gloves and stockings. In the twentieth century, the houses of the Christian Dior level themselves decided whether to refuse a client a dress or not, so that not every woman could order an outfit. The screenings themselves were held exclusively as client events: both Christian Dior and Coco Chanel, for example, drove out journalists who tried to sketch models from the catwalk. Then there was no prêt-à-porter, much less a mass-market, and everyone who had it emphasized the wealth. Now we put on sneakers even on our own wedding, we buy T-shirts instead of silk blouses with jabot and we wear things from Zara and H & M along with Chanel things. Modern fashion does not dictate to women how they should look, but tries to understand what these same women want. At the same time, the couture divisions of the brands continue to dress the clients in insanely expensive dresses, and this is a problem - and for the brands themselves in the first place.

In fairness, brands have no particular choice: haute couture must be sold. To sell to someone who has money - and a lot. The Wall Street Journal writes that among the clients of the atelier there are young American women from big business, there are “old European money” - girls who were brought by their mothers in the studio of haute couture, and those by their mothers, and so on. But not a single publication denies that the bulk of customers of today's couture are from Asia, Russia, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and more recently from India and Africa.

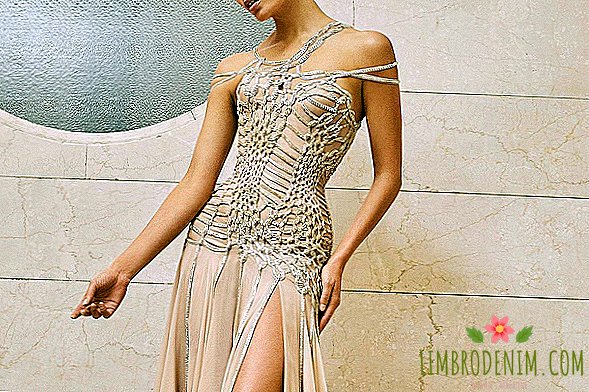

When you see a Russian oligarch or an Arab sheikh’s wedding on the Internet, it’s almost always haute couture, and the most concentrated: according to The Luxonomist, ten to fifteen images can be ordered for an Arab wedding guest, on average, Arab customers order about thirty dresses in season. Even at minimal cost, this is one and a half million dollars only for haute couture - not counting the prêt-à-porter bags, shoes and clothes that one such client can buy additionally. It would be strange not to be guided by her ideas about the beautiful when creating couture collections, which were originally invented as a client-oriented business.

This explains why the majority of haute couture collections consist of weightless dresses embroidered with flowers, reminiscent of Disney princesses: they are beautiful and understandable beauty, they are feminine in the conventional sense, which means that they are easier to sell to clients from countries with patriarchal ways — men with very traditional ideas about how a woman should look like. Elie Saab and Zuhair Murad generally built a business on this, and a very successful one: almost 50% of Elie Saab’s sales are haute couture, which also includes wedding dresses - their brand makes about three hundred a year. All - by the individual order. Compare with Jean-Paul Gautier’s 60-80 couture clients: the designer himself calls this number, and although it is small, he continues to do the old-fashioned haute couture, which is more about creativity and self-expression than about the fashion or tastes of most of the richest women.

What to do in this situation for brands that want to associate not with Disney, but with current fashion processes, and at the same time earn money, is unclear. “Haute Couture gives our business what can be called the very essence of luxury. In contrast to the money we lose, thanks to couture, we gain an image. See how much attention the collections attract. So we show our ideas,” said Bernard Arnaud, owner of the group brands LVMH, which includes, for example, Christian Dior.

But this is only partly true. No major brand can afford to fall in haute couture sales, and when after the departure of Simons from the same Dior they fell by some 1%, everyone wrote about that. In order not to give up the slack and not to spoil their reputation, the brands are forced to twist their snakes and balance between those same tulle dresses and something fashionable, but wearable. Again, Dior has now hired Maria Grace Curie from Valentino, who was famous for his successful couture style - you definitely saw his embroidered dresses and minimalistic capes. Kyurie says that she is “trying to find a balance between fantasy and commerce” - and she does all the same fairies of the dress, balancing them with classic “Dior” costumes. And Pierpaolo Piccioli, who remained in Valentino, turned out to be a minimalist and showed a collection of very beautiful laconic things. And although the critics praise his work, it is unclear whether the risk was justified: the demand for embroidered dresses in this price segment is much higher than for architectural comme il faut things.

What is happening now, returns to talking about the role of couture in the coordinate system of modern industry. Massively talked about this after the first collection of Raf Simons for Christian Dior. The designer then showed the dresses familiar to everyone from the series “The Most Chic Woman of the Planet”, but he also added simple wearable suits, coats, sheath dresses — and many. Reviews in the press were different - from enthusiastic to "This is not a haute couture!". Such an approach by Simons marked a sharp change after the era of crinolines (on the one hand) and pure creativity (on the other), which thanks to John Galliano, Alexander McQueen (although he was not an official couturier), Martin Margiela, Christian Lacroix, Jean-Paul Gautier and other renowned designers have defined the haute couture look of the last decades.

With them, couture really was the quintessence of brand ideas, the flight of thought and a source of inspiration. Now, of the old-timers in this spirit, only Gotye and Galliano work in the Maison Margiela. John makes art collections with varying success, and the owner of the brand Renzo Rosso deliberately does this: he wanted to hire an artist and hired him, creating a kind of exception to the current state of affairs. But what is happening since the beginning of the 2010s clearly signals a commercial vector: a whole division with a very expensive and long production cycle for brands is too unprofitable if it cannot be earned on it. In addition, prêt-à-porter continues to approach in terms of cost and level of performance to couture, and its brand allows itself to do just underlined relevant - in any case, much more fashionable than the actual couture.

It turns out that haute couture goes back to basics, but with an amendment to the fact that a century and a half has passed and we live in a completely different world. The question of what a brand, which claims to be the most authoritative in the fashion world, can and cannot do in this segment, is not really about clothes. On the one hand, no one has the moral right to make claims to couture brands that honestly target customers from Africa, Asia and Eastern countries: business must make money, plus in their reading haute couture remains a demonstration of outstanding manual technicians. On the other hand, this has nothing in common with today's agenda, and a fashionable brand, if it is really fashionable, cannot afford retrograde. So historic fashion houses exist between this hammer and the anvil, selling dresses for the price of cars. Nowadays, young brands like Zuhair Murad feel much more comfortable. They immediately occupied a very narrow niche and do not have to worry about whether the fashionable press regards them as the embodiment of good taste. And in the end, there is nothing wrong with dresses for Arab princesses.

Photo: Atelier Versace, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Victoria and Albert Museum