"What's wrong with your face": How I live with Parry-Romberg syndrome

Parry-Romberg syndrome - a rare pathology, the genesis of which is still not fully understood by physicians. A person with such a disease atrophies the muscle and bone tissues of one half of the face (there are fewer cases where the disease affects the entire face). The disease develops slowly: first, the skin and subcutaneous tissue, as a rule, atrophy, then muscles and bones. In this case, the motor function of the muscles is usually not disturbed. Atrophy most often occurs in the lips, eyes, nose, and ears. Less often, it affects the forehead, palate, tongue, and even less so - the neck and other parts of the body.

The disease can be congenital, and can develop against the background of intoxication, infections or physical injuries. As a result of these processes, the face is deformed and acquires an asymmetric form: the side affected by the disease is less healthy. Sometimes the development of the disease is accompanied by a decrease in the sensitivity of the skin, its depigmentation, loss of eyebrows and eyelashes. We talked to the heroine, faced with this state.

Very often I hear the question: "What about your face?" How to answer this, I do not know. I had no head injuries, my parents did not beat me, and I was not born that way. The deformation of my face occurred somewhere in two years - that is, not instantly, as some people think. Why Parry-Romberg syndrome chose me exactly, so far, no doctor has said for sure. The alleged cause is trauma in childhood. When I was six years old, we played some kind of active game with my older sister, and I broke my arm. I was put in the hospital. After a while, eyebrows and eyelashes fell out, and a barely noticeable red speck appeared on the cheek, which parents took for lichen. Then no one - neither me nor my family - suggested that this would be a serious incurable disease.

Shortly after a broken arm, constant aching pains appeared. The bones of the arms and legs were especially painful - it seemed that someone was twisting them. I still had a headache, I could not eat, fainted, I vomited. Something similar, it seems to me, happens during an epileptic seizure. At the same time, the face, as often happens in people with this disease, did not hurt. Is that sometimes felt barely noticeable muscle tremors.

I hardly remember my childhood, because I spent a lot of time in hospitals. Then I was constantly pulled out of a comfortable, suitable environment for me - they sent me to the hospital of the next departments of hospitals. It seemed to me that in each new department I lay the longest. Perhaps it was so, because the doctors could not understand what was happening to me, and were not in a hurry to allow me to leave the hospital room.

The deformation of my face happened somewhere in two years - that is, not instantly, as some people think

Mom took me to different specialists, and they all shrugged their shoulders and could not make a diagnosis. Since too much time has passed since that moment, I don’t remember much. I think that the period of my life was more terrible for my parents, because it was the 90s, and my family lived very poorly, there were no good doctors in Irkutsk.

My mother and I visited the endocrinologist, oncologist, rheumatologist, dermatologist, but they all could not make a diagnosis. Mom was in despair, so she decided to try unconventional treatments. We went to fortune-tellers, who saw the cause of the disease in fear, healers - they tried to remove damage from me with the help of red wine and the priest - he let go of the original sins and saw the problem in that the parents were not baptized.

After all this, we finally met a competent specialist, he was a neurologist from the Irkutsk Regional Children's Clinical Hospital. She sent me for a biopsy and for consultation at the Research Institute of Rheumatology of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences. There I was diagnosed with Parry-Romberg syndrome, prescribed medications that I had been taking for many years. When they ended, they had to be ordered in Moscow - in Irkutsk there was simply no necessary medicine.

A year later, I felt much better, I wasn’t screaming from the constant aching pain in the bones, I could eat - and this means that the drugs really helped. I began to go to hospital for inpatient treatment much less frequently - about once a year. The most unpleasant there for me was the daily inspection. The head of the doctor took an outpatient card and read out records about the course of the disease, and the students of the residency listened to her. Since my disease is rare, I always felt the special attention of doctors and medical students. I think that then my childish psyche was a little traumatized. Every time the doctors conducted the examination, I silently looked at them and did not react at all, I felt like a guinea pig. But over time, hospitals have become a familiar environment.

I was lucky with the doctors I met in Moscow. They did everything possible that, in principle, Russian physicians were able to do at that time — they diagnosed, prescribed effective drugs, confirmed disability, which greatly helped in purchasing expensive drugs. When the disease progressed, there were good people near my family who did not refuse to help — relatives, colleagues, mothers, family friends. They gave money for a trip to Moscow. I am eternally grateful to my mother, and I can’t even imagine what effort she shouldn’t give up on me at that moment.

Remission came at ten years old when I went to fifth grade. I returned to the same school where I studied before. There were no more seizures, though, sometimes there was a aching bone pain that I still feel. I received the same therapy. Over time, I began to stir up the pills, I just threw them away, afraid to tell the doctor that I feel bad. Then I did not know that all the most difficult tests are still ahead, because the deformation of the face by that time was already very noticeable.

We went to fortune-tellers, they saw the cause of the disease in fear, healers - they tried to stop me from damaging with the help of red wine, and the priest - he let go of the original sins

I studied in a good school, so I was not subjected to any systematic harassment. But I still felt that my peers did not treat me like an equal. In middle classes I had the nicknames Baba Yaga and Terminator. It is good that my sister studied at the same school - she always protected me from offenders. Then I realized that the environment can be aggressive, I loved to spend time alone, read books and dive into my world. It was difficult for me to make friends until the age of fourteen.

When puberty began, I, of course, wanted to like it. Like my peers, I tried to look attractive, but there were situations when, instead of a compliment, I heard the phrase: "Why are you so terrible?" Most often these were men who wanted to meet on the street. As a rule, they all uttered this terrible phrase as soon as they saw my face.

When I was eighteen, I received a quota that allows for operations at the Central Research Institute of Dentistry and Maxillofacial Surgery. In total, there were six surgeries; I had several facial implants installed and also corrected the shape of the nose and lips. I remember how I waited for every next operation - it seemed to me that she would make me happier, although not all of them were easy.

Starting from the third operation, I began to feel the effects of anesthesia and how implants survive. It was also psychologically difficult, because I definitely couldn’t work with the result. At first I liked everything, then it seemed that it could have been better. And I saw a lot of people who understood that after the operation they look noticeably better than before it, but at the same time they suffer from the fact that they don’t look like they dreamed of. Probably, at first, I, too, was ready to go to the operating room as many times as I wanted, but then I realized that this is not the only possible way to happiness and the meaning of my life is not constantly correcting myself, it’s not worth spending time on it.

At 19, I went to study in Moscow. It turned out that it's easier to get lost in the crowd. Only after the move, I realized that in my hometown it was the hardest for me at times when I was getting to some public place. These places themselves did not frighten me, but the road to them was a test. And the same thing is happening now: when people meet, they do not perceive me as a person. I am an accessory for them. They can look and evaluate, not considering how correct this is. It is the passers-by who most often allow themselves to ask stupid questions or insult.

Now this also happens, and in such moments I do not like myself. For example, a couple of years ago, a relative of mine met me at a wedding with friends. He told me: "You're so cool, but how can I show you to my mom?" I think he meant it was my appearance, and not something else. Yes, it sounds strange, but in Moscow it happens all the time - in bars, in the subway and other public places people can look at me, try to touch my face, look under my bangs. Please do not touch me usually does not work.

Previously, I was helped by such a psychological device: when I looked at my reflection, I imagined that I was only one healthy half of my face, and the second, affected by the disease, was someone else, it was not a part of me. I used this trick to not be afraid to go outside. Now I try to perceive myself as entirely as I am, although it is very difficult and not always possible.

Psychologists have often tried to help me in this in childhood and adulthood, but they never asked me how I perceive myself, whether my peers hurt me and what I feel at that moment. I remember once at a consultation a psychologist asked me why I pretended that I had no problems. I was then twenty years old. I think that even then the necessary moment for discussions with a specialist was missed, and I established a sufficiently strong barrier to such conversations with someone else.

Instead of a compliment, I heard the phrase: "Why are you so terrible?" Most often these were men who wanted to meet on the street

Therefore, I believe that any surgical intervention should be accompanied by psychological support. At the same time, the specialist should work not only with the traumas of the past, but also with expectations from the future. Before the operation, it is important to understand that the surgeon is not a magician and there is no need to expect anything supernatural from him. I always tried to remember this, but all the same there were experiences, and I really lacked the opportunity to share them immediately after operations.

In the family, the subject of my illness is considered taboo. We never discussed what happened to me when the disease progressed and my appearance changed. Parents are still embarrassed to discuss this with me. At one time I also wanted to think that there was no disease, but now I am trying to understand what was happening to me, and I try to accept myself as I am. Friends support me, but sometimes they may even ask the question: “Would you like to correct something else?” No, I do not want to, because in this case I will spend my life trying to become impeccably beautiful for those who see me as a curious object - are they examining a face or asking: "Accident?" I really want to love myself always, but it is difficult, because strangers constantly remind me that I do not look like them.

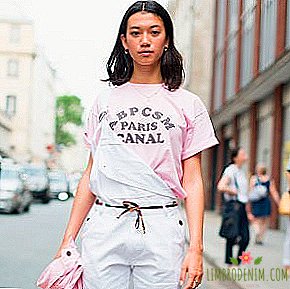

Photo: Alla Smirnova