How has the role of makeup in the life of a woman

In 1969, the second-wave feminist Carol Hanish wrote an essay later entitled “Personal is Political” by publishers, essentially the answer to her colleague in the feminist movement, Dottie Sellner. Hanish drew the attention of readers to the fact that in the left-wing radical movement it was not customary to pay enough attention to the "women's issue": the pressure of beauty standards, the right to abortion, the division of responsibilities in the family. Political groups considered this to be personal women's problems, for the solution of which there were meetings of politically active women discussing their relationship experience (something like “group therapy”).

It was believed that if a woman talked about her problems with her friend and agreed with her husband that they would wash the dishes in turn, the topic was exhausted. Hanish wondered: what if the obstacles and troubles that women face in their lives are not explained by each individual's erroneous choice, but follow from the way women educate and perceive? Moreover, can personal choice be the result of a large social policy and influence it? In this context, all means of expression, including makeup, can be a political statement.

In the Edwardian era, the lady of high society did not rely on obvious makeup (at least the heroines of Downton Abbey now remind us of this); prominent actresses and prostitutes. The rest of them used perhaps that cream blush, which painted the cheeks and lips, and matte shadows; About red lipstick and speech did not go. It is noteworthy that in the 1910s it was her, lipstick, suffraggists, who fought for their right to vote, were chosen to demonstrate emancipation. The trick worked - in 1912, so many women with bright lips came to the protest march in New York that the state could not ignore it, and the suffraggists won their voices along with the right to paint themselves. The production of cosmetics developed during these years: they invented lipstick in a tube and mascara, and in 1909, Harry Gordon Selfridge began to sell cosmetics openly.

After the end of World War I, together with economic growth, the right of women to vote and jazz appeared flappers. The girls, who were protesting against the old social foundations, sat behind the wheel, smoked, drank, cut their hair short - that is, they did everything that had previously been allowed only to men. They wore knee-length skirts - by the standards of time, very short - and they were brightly colored, as if trying to isolate themselves as much as possible from the Victorian girl with her natural, gentle face. Flappers painted their lips and eyes dark, plucked their eyebrows, finished the shape of their lips and eyebrows. They refused to spend their youth, sitting in their father’s house and waiting for them to be married, to behave modestly, “as befits girls” - and expressed this, including through appearance. With the onset of the Great Depression, there was no place for frivolity and rebellion, but the Flappers managed to change the idea of what a woman is capable of.

During World War II, the idea of makeup as a way to express oneself was picked up by the state and used to motivate women in the rear to work for the good of the country. Given that economic conditions did not leave the possibility to decorate themselves with clothes, women began to do bright makeup and complex hairstyles from the multitude of victory rolls. The US Military Directorate decided that the lipstick supports the morale of the nation, and Elizabeth Arden, in agreement with the US government, released a series of cosmetics for women serving in the Navy, with a victory red shade lipstick.

The fifties were not interesting from the point of view of ideological makeup. After the war, the soldiers began to return home, and women occupying the jobs of men were not needed. The concept of a housewife has become popular: it does not work, but is engaged in self, home and family. At the same time, the cosmetic industry developed and grew rich, but no political makeup - at least, massively - did not carry.

Signed for the sixties, the "London image" - in simple terms, makeup in the style of Twiggy - had more cultural implications. The fashion of the sixties was influenced not only by pop art and op art (optical art), but also by postmodernism - Bart writes that the author is dead, Piero Manzoni sells his shit in jars. An excellent background for experiments with the framework of what is permitted not only in clothes, but also in make-up. But in the same sixties, hippies appeared who were fleeing the capitalist society of consumption and well-being in all possible ways, including refusing cosmetics.

In the feminist discourse from the seventies to the two thousandth, beauty standards imposed by society were an important topic. Naomi Wolfe, third-wave feminist and author of The Myth of Beauty, wrote: "The skepticism of modernity disappears when it comes to female beauty. She still - and even more than ever - is not described as something defined by mortals, shaped by politics, history and the market system, and as if there is a higher, divine power that dictates immortal writing about what makes a woman pleasant to look at. " In some sense, the book Wolfe sums up a very long discussion about the beauty myth: from the late 60s to zero (in other words, the entire second and third wave of feminism), girls, refusing to make themselves beautiful for the sake of society, completely ignored makeup.

In the seventies, the main fighters for freedom of expression became punks. It is not surprising that the subculture, which grew out of punk rock fans, expressed itself (and continues to do so) through appearance. A gloomy or deliberately bright make-up - a lot of shadows, eyeliners, burgundy lipstick - protest against the boring, prosperous and measured life of society. What the hippies fought with love and a return to nature, the punks met with heavy music, dark, challenging make-up and aggression. In the punk culture, it is interesting that over the years she has a lot of branches, each of which has its own makeup culture: from pastel punk with obligatory hair of "mermaid" colors to gothic punk with the maximum amount of black.

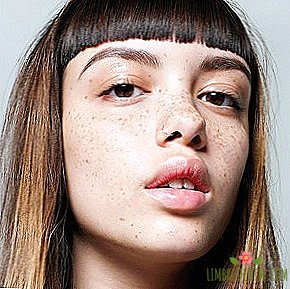

In cultural studies and sociology there is the term "reappropriation" - the process by which a group regains words and phenomena that were previously used to oppress this group. So, gays and lesbians in the 1980s reapproved the words "queer" and "dyke" - they can be translated into Russian as "fagot" and "lesbukh." They said loudly and proudly: "Yes, I am a fagot. Yes, I am a lesbian. I have nothing to be ashamed of." In modern society, the same is happening reappropriation of cosmetics. Now girls are often painted neutral (almost like in the Victorian era), within the framework of the idea “my face but better”, emphasizing their own natural beauty and self-sufficiency. Modern feminists, on the contrary, continue the tradition of lipstick feminism and use make-up as a means of self-expression: "unsuitable" colors, "vulgar" makeup, all this purple lipstick, green arrows and hypertrophied eyebrows - this is not "my face but better", it is "my face is not your business. " One can say women return their appearance to themselves - if feminists of the second and third waves refused to be beautiful in the understanding of the patriarchal society, then modern equate beauty with individuality and name all that is considered beautiful: bright yellow lipstick, unshaven legs or pink eyelashes. It turns out that a woman is beautiful because she considers herself as such, because all people are beautiful, because there is no beauty as an objective category.

Photo: cover image via Shutterstock, 1, 2 via Wikipedia Images and The Metropolitan Museum of Art