As I went to Princeton to study the medieval Middle East

In 2014, I graduated from the master's program at the Moscow State University. and immediately after that entered the graduate program there too. Before that I went to study abroad several times. First, at the American University of Beirut for two months: then for the first time I realized that I could compete with graduates of foreign institutions. Then there were two months in Paris at the National Institute of Oriental Languages and Civilizations, where I did mainly my master's thesis, and, finally, a short trip to Tel Aviv, where I taught Hebrew.

I’m not interested in being the only specialist in all of Russia for anything, I want to be part of the global scientific community

Already somewhere in the middle of my first year in graduate school at Moscow State University, I realized that it did not suit me: I did not feel professional growth. Therefore, at first I went on a research trip to Israel and began to collect documents for admission to different American universities. I chose the United States. Europe did not suit me, because there the approach to graduate school is similar to the Russian one: for three years, and from the very beginning you sit down to write a dissertation. No study, only scientific work - and I had a desire to learn something else. Britain pushed the high price, because getting to Oxford or Cambridge is not so difficult - it is much harder to get money for it. Before that, I already had the experience of enrolling in the magistracy of SOAS - the School of Oriental Studies and African Studies at the University of London - where I was ready to be taken, but I did not have enough money - one training would be worth 16 thousand pounds.

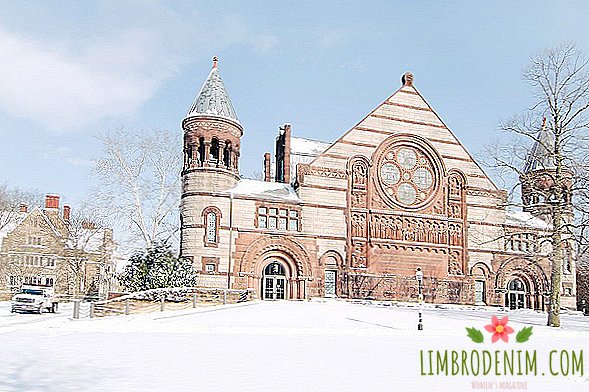

American programs are good because, firstly, they involve very serious studies in the first two years of graduate school, and secondly, there are very generous scholarships. Middle Eastern studies in the US are popular, so there are many programs. I applied to Canadian McGill University and to four American universities - Chicago, New York, Columbia and Princeton. And I was in full confidence that I would go either to Chicago or to New York, and sent the documents to Princeton just to be random. It all happened the other way around: the first four universities refused me. A letter from Princeton with a positive response came the latest. I still remember that day - it was just a miracle. I was in Tel Aviv, I was sitting at a lecture - when this letter arrived, I ran out of the audience and started calling home.

The selection to Princeton is carried out in two stages - first on the basis of the documents submitted, and then subsequent interviews. I could not come in person, so they talked to me on Skype. I must say that the interviews are very intensive: they check both scientific knowledge and language. I had two language and one scientific. At the last 40 minutes, the professors talked with me, and they seemed to take me to work: for example, they asked me why I wanted to visit Princeton. Although it is even funny - Princeton! When I was asked this question - and they knew that I was already a graduate student at Moscow State University - I replied that I felt isolated. I’m not interested in being the only specialist in all of Russia for anything, I want to be part of the global scientific community.

Now I am studying in the second year of the postgraduate program at the Faculty of Middle Eastern Studies. The path to the topic of the thesis was long and thorny, but I was lucky with the teachers, who were very open and always supported me. Over the past year, I have turned from a specialist in new history into a medievalist. There is nothing surprising in the fact that I changed the direction: here it can be done during the first two years. This becomes impossible after passing the candidate minimums. It will happen to me in the fall of the third year, and before that I want to recruit more narrow specialized courses.

Now I would really like to say that all my life I wanted to deal with the medieval Arab East. Even my first coursework in the ISAA was dedicated to him - I wrote it on medieval geographic literature. Then I really liked it, but it still seemed to me that I did not know Arabic well enough to work with medieval sources. Arriving in Princeton, I immediately took a course with Professor Michael Cook, who teaches how to work with materials of the Middle Ages, with the living language of those times. And then for the first time I realized that I could work with these texts.

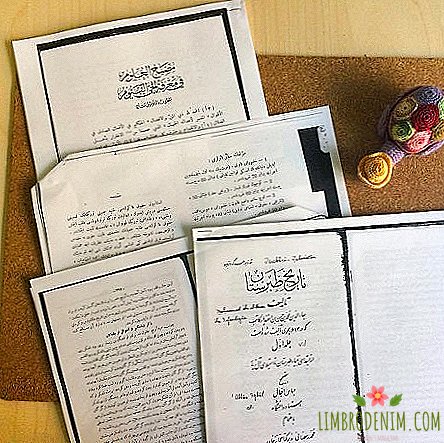

Then I signed up, for purely romantic reasons, for a course in Arabic paleography — it is impossible to learn Arabic and not be aware that there are Arabic manuscripts and calligraphy. For me it became love at first sight. I realized that if there were no Arabic manuscripts in my dissertation, it would be a waste of my time and intellectual potential. This was the beginning of my move towards the Middle Ages - from the final work on that very course and the proposal of the professor to write a scientific article. Then I realized that I would rather make a good dissertation than a bad article. My path was rather ornate, but it seems to me that I found what I want to do — the Zaydite community that lived in medieval Yemen.

For the first year, I outlined my topic: the Zeidit Imamate of the 15th-17th centuries in Yemen, or rather, his historiographic school. I am interested to know how they described their history, interacted with other historians. The Zaydite community itself is now a developing trend in Arabic, and very little is known about it. Let me explain what Zaydism is: it is a separate branch of Shiism, the study of which began relatively recently. Now a whole galaxy of prominent scientists, many of whom are in Princeton, is engaged in the history of Zaidism. This is, for example, Princeton graduate Nadjam Haider (now a professor at Columbia University).

Many very interesting stories are connected with this community - for example, as two Zaydit communities, in Yemen and Iran, interacted. By itself, the 15th century Yemen is a very curious and at the same time little-studied place. XV-XVI century - this is the time when the Portuguese first sailed to Yemen and discovered a flourishing state with connections throughout the Indian Ocean. I want to talk about the intellectual life of this place. Now, when we say "Yemen", we imagine a beggar-ridden country, which has been bombed by the Saudis. This is not quite true even now - modern Yemen does not boil down to what is shown on TV, and even more so this is not true of Yemen of the fifteenth century. There was a vigorous life, people wrote books, poems and traveled. At the same time, medieval Yemen is one of the few white spots in modern arabistics, and each manuscript carries a small discovery. Therefore, it is very pleasant to work with them: you feel like a 19th-century Arabist, when it all began.

Here, in Princeton, a small town, there is almost nothing but a university. But living here, you feel that you have your hand on the pulse of the intellectual life of the whole world, because invited teachers constantly come. There are generous grants at the conference - as a graduate student I can go to any, and not necessarily to speak, but just to listen. Here you really feel that you are part of something important. Last year I met with baboutmore specialists in different areas of my field than in all previous years of study. At the same time, I almost did not leave Princeton anywhere - they came here, and all of us - not only the teachers, but also the students - had the opportunity to meet them. Also here are very actively developing projects on digitizing texts and maps. In addition, at our faculty more than half of the students came from other countries, and there are also quite a few foreigners among the teachers.

Under US law, universities should be open to all. But the same Princeton began to accept women in graduate school not so long ago, only in the 60s. There is a problem with racial diversity at the reception. Nevertheless, the official policy of the university (and this is written in all the fundamental documents) is openness for people of any nationality, orientation, gender, origin. But I find it hard to judge how this works, because I myself am still a white girl. I can only say that I have not encountered gender issues. I haven’t heard any complaints from my friends of Asian or African origin either. On the other hand, last year there were mass protests demanding the renaming of one of the faculties, named after Woodrow Wilson, because Wilson was a racist. He was never renamed, but the university issued several lengthy statements that he would change his attitude towards the president’s legacy. What it will pour out is hard to say.

I would like to convey to others the sincere astonishment of the Arab and Islamic culture that I myself feel.

In principle, the American teaching system is friendlier to the student than the Russian one. The teacher is not the ultimate truth. The student is expected to work actively, and the teacher is more likely to sit in the classroom, not in order to put the material into the student, but in order to discuss the information. As a result, it is more sympathetic to what the student is doing.

As for openness, I do not leave the feeling that in Russia women are treated differently. No, I did not hear in my address any insults, but, for example, no one understood why the girl was learning Arabic. I had conversations with teachers about the fact that I want to do science - they rolled my eyes at me and asked: "What is it?" Throughout the six years that I spent at the ISAA, I heard many times that before the girls were taken there, only "so that they do not smell of boots," and sometimes I myself felt that I was there rather as a decoration. I have no doubt that no one specifically wanted me to be evil, but the atmosphere was different. There is no such feeling here - for example, no one will tell me that why should I, my dear beautiful girl, spend the best years of my life on dry science.

When I lived in Russia, I had little thought about the problems of feminism - probably, not least because of the mass ideas about feminists. Here I think about it, despite the fact that no one specifically pushed me to this topic. Although talk about the rights of women in the United States are very active and with purely American detail. Americans generally like to chew everything up to the smallest details - for example, recently at a training for beginning teachers we were told that a year ago at the same seminar, half an hour had been spent discussing with students that a teacher could not meet with his students except in professionally. It would seem that there is to discuss: they said no - it means no.

Two years ago, for all novice teachers and first-year students, the book by psychologist Claude Steele "Whistling Vivaldi. How Stereotypes Affect Us and What We Can Do" about how to keep track of what you say and how you behave will be perceived, primarily in the classroom. There is such a psychological phenomenon as the threat of confirming a stereotype. If a person feels that others judge him according to clichéd ideas (he doesn’t even have to specifically indicate this, it is enough to create an environment in which he will think about it), then he will start to learn and work worse. American universities consider such information important for their students and teachers, and I am afraid that the Russian education system is very far from this.

Sometimes I ask myself why I do arabic studies. I would say that my most important goal is to show that we can still understand another culture or try to do this by climbing through the stream of distorted information. I do not think that this is a meaningless work, that few people will read a scientific monograph outside the academic world — yet a huge amount of popular science literature is written in America, and the scientists themselves write it. And if such books, small and accessible, will be read by people who are not specialists, this will already be a point in our favor.

I do not know how well you can understand another culture, its deep features and logical connections - but I believe that we can learn to appreciate it. To understand that it is not at all necessary to be the same in order to respect each other, that the value of human history lies in the diversity of cultures, languages, choices that different societies make when trying to arrange their lives. I’m probably not going to write this in the introduction to my first book — I’ll just be ridiculed — but I try to keep this humanitarian message in mind. I would very much like to convey to others the interest and sincere astonishment of the Arab and, more broadly, Islamic culture and civilization, which I myself feel.

Understanding is important: for example, in order not to get angry at the Muslims who blocked the Prospect of Peace in Kurban-bayram, knowing what this holiday means to them. At the same time, no one calls on us, the Arabists, to convert to Islam or to penetrate to it with some kind of special love. For example, someone may be annoyed by the call to prayer - but I am sure that he will be less annoyed if you imagine what it is. These are very beautiful words: that all of us, people, are mortal, that there is a god, and we must sometimes show respect for his power.

What scares me most of all in my compatriots is this terrible misunderstanding of other cultures - when a taxi driver, passing by a new cathedral mosque in Moscow, says that it is a shame for Russians. And why, actually, a shame? Muslims in Russia did not appear yesterday, this community is already several hundred years old, and they are the same Russians as we are. I really respect Western countries for leading this discussion, albeit with many excesses. Here I will not hold back and advise the recently published book "What is Islam?" - it is written very simply and clearly, and it is worth reading to anyone who wants to understand anything about Islam.

The problem of the science that I do is that you are always asked to explain the present. A well-known English Arabist Robert Irwin, an expert in Arabic literature, the author of the commentary on “1001 nights” joked on this topic very successfully, when he was once again asked about ISIS. (organization is prohibited in Russia. - Ed.). He said: "To ask an Arabist about ISIS is like asking a Chaucer specialist if Britain will come out of the European Union." But this duality is inherent in the history of arabistics as a science, and we cannot avoid it. In the meantime, I talk about my research blog. I started with travel notes when I went to Beirut, but after moving to Princeton, I focused on science and student life.

Photo: Flickr (1, 2, 3), personal archive